In my post about our recent biking, I promised a separate post about the Ohio and Erie Canal per se. True to my word…

I’m not going to try to regurgitate all that has been written about the canal and its history. Use the link above for a Google search page of sites about the canal. Instead, I want to offer what I saw of it and my impressions. I learned any history that I include here from Interpretative Rangers or the various informational signs posted throughout the park.

The name Ohio and Erie Canal stems from the two ends of the canal: Lake Erie and the Ohio River. By connecting the two, commerce was enabled between Lake Erie and the Gulf of Mexico. It turned Ohio into the third wealthiest state.

The canal was a huge undertaking! It was dug entirely by hand in the 1820s and completed in 1832. It was specified to be a minimum of 40 feet wide at the top and 26 feet wide at the bottom, with a minimum depth of 4 feet. The canal was used for cargo until 1861 when rail transport took over. From the 1870s it gradually degraded until 1913 when massive storms damaged much of what was left, and lock #1 had to be dynamited to allow flood waters drain.

We rode along 25 miles of the tow path, from the southern end of Cuyahoga Valley National Park to the northern end. In the southern end it is hard (for me, impossible) at times to discern the path of the canal. Gradually, the outline of the canal becomes visible as a large dry trench. Much of the tow path is between the canal and the Cuyahoga River. Toward the northern end, the canal still holds water, although probably no longer four feet. I was told that some industrial sites still draw water from the canal.

I don’t know how many locks were originally in the region we biked, but we saw many—again, mostly in the northern half. Canal barges were specified to be a maximum beam (width) of 14 feet and length of 85 feet. Although the canal trench was specified to be 40 feet wide to allow boats to pass each other, the locks were much narrower averaging only 15 feet wide and 90 feet long, thus fitting only one boat at a time.

The lock gates were massive wooden structures, some operated by hand, others by horses or mules. The average lift capability of the locks was 9 feet, with the largest (called the “Deep Lock”) being 17 feet.

I wasn’t able to find any sign of the pumping equipment they would have needed to manage the water levels in the locks.

Near the north end of the park is the Canal Exploration Center, a CVNP visitor center. The exhibits are very well done! Stop in, if you’re in the area.

At the CEC is a restored lock with the gates in place.

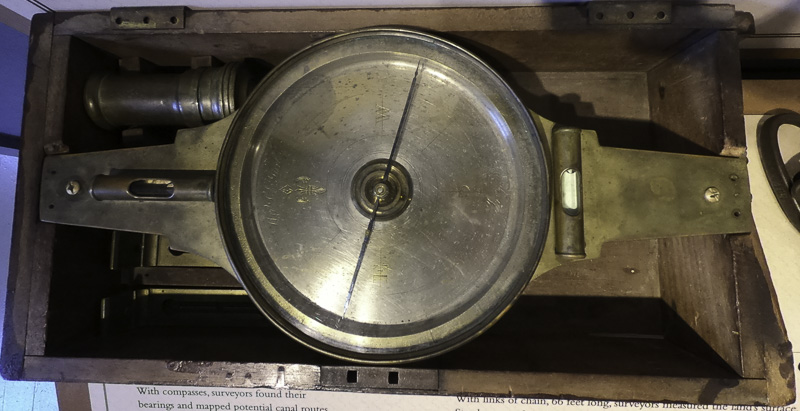

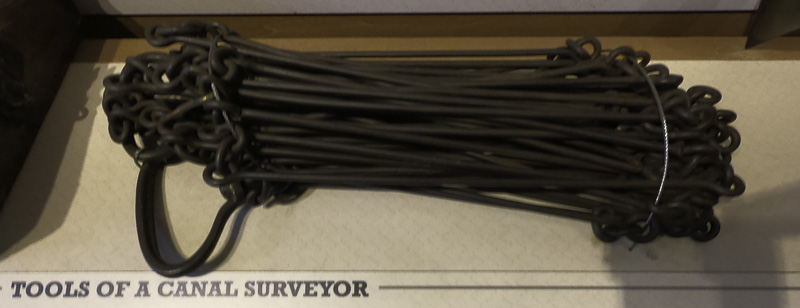

In this era of GPS location accurate to a few feet and laser transits, it was sobering to think back about the tools available when the canal was built.

At the Canal Exploration Center I found this modern flood control device; it had valves that would send canal water into a side arm of the Cuyahoga River.

This is fascinating Al. I love the history of the canals. We always make sure to see the tow path on the Delaware and I can picture the mules in my mind. Interesting times and the labor involved is amazing. Good post!!

Great info on something that is probably obscure to most Americans. Your adventures in this area make me want to explore it myself someday!

Also a canal fan. Check out C&O canal when you’re in D.C. It has been repaired and managed for many decades after suffering the same fate as the Eire.

FYI – There are no pumps for the water levels. The locks fill with water from upstream and empty it downstream with theIR opening and closing, also powered by mules. https://www.nps.gov/choh/index.htm

Not the most accurate accounting I’ve ever read. There are a number of good, interesting books that could inform you a bit.

Deep Lock had a 12 foot life.

A P & O Lock in Kent reportedly had a 19 foot lift.

The Ohio Canal’s name was officially changed to Ohio & Erie in an Act of the legislature in 1849. Nobody really used the ‘new’ name until recently.