Early on in our trip planning, White Sands National Monument was on our list. But then we decided that we’d like to see some of Utah “before it got too cold,” so we planned to go west on I-40 all the way into Flagstaff and then north. We decided that we’d do White Sands, NM some other time.

Well, “too cold” seemed to be following us all the way across the country (local temperatures were often 15° to 20° below normal—we started to think that it was our fault!). We decided that we would drop down to a more southerly, i.e., warmer, route—I-10—after Bosque del Apache. Yea! White Sands was back on the route!

We knew that there are basically two “White Sands” things. There is White Sands National Monument, and also White Sands Missile Range, the largest military base in the country in terms of area. The Missile Range is closed to the public (of course), so we focused our imaginations on the Monument, which we thought was completely separate.

It turns out, it isn’t so separate. The Monument is completely inside the missile range; it closes to public access any time the military launches a missile. Phew!

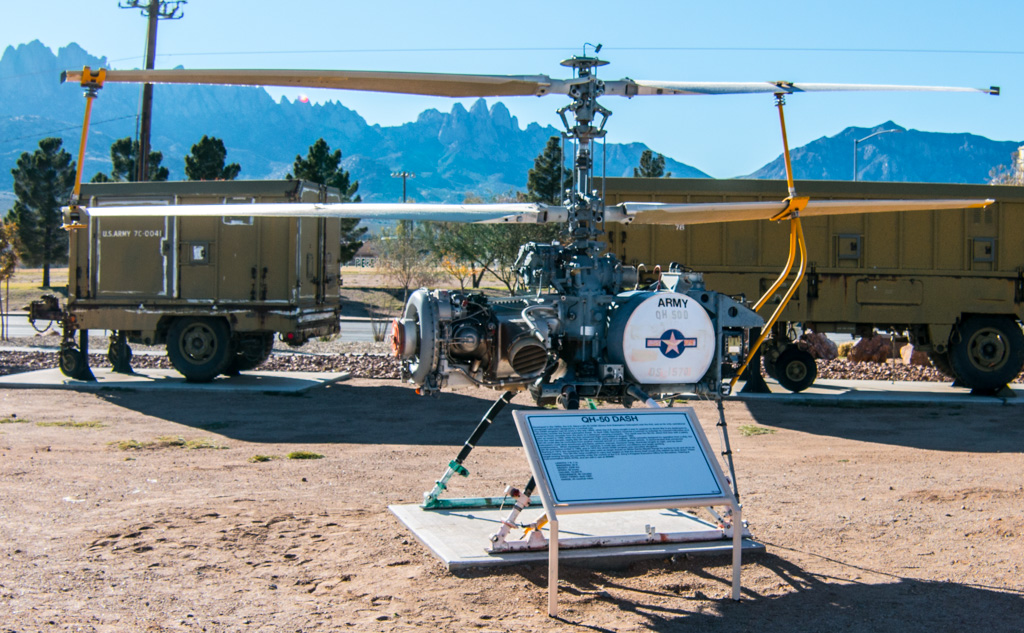

The other thing we didn’t know was that the missile range has a museum open to the public! Did I mention in a previous post that I like space-oriented things?

White Sands Missile Range Museum

The first day, we went to the museum. Since you’re entering a military base (by all of about 100 yards), you must present ID, and they run a quick check with the FBI to see if you’re a baddie. (Sorry, no pics of the entrance station where we had to register. That is apparently a serious no-no.)

Outdoors display

We spent most of the time at the museum outside at the rocket display. It was neat to actually see some of the rockets whose names I knew from the ’60s.

The rockets on display here were almost all developed for the military, but they also enabled our manned space program. Until the Apollo program’s use of the Saturn V booster, all of the rockets used for our manned space flights were repurposed military rockets—Redstone, Atlas, and Titan. The Redstone held a special place in my memory because it was used for Alan Shepard’s and Gus Grissom’s sub-orbital flights at the start of Project Mercury, the beginning of the US manned space program.

I didn’t know that the Redstone was designed to be “transportable.” From the information sign in front of the rocket:

As a field-artillery missile, Redstone was mobile and transportable by plane, truck, or train. However, when on the move, it needed a convoy eighteen miles long, with 200 vehicles carrying approximately 10,000 individual pieces of equipment and more than 600 men. The Redstone itself was carried on three trucks—its nose section (warhead), midsection (power plant and fuel tanks), and tail section—to be assembled in the field.

Transportable? Maybe. Stealthy? No way!

Indoors

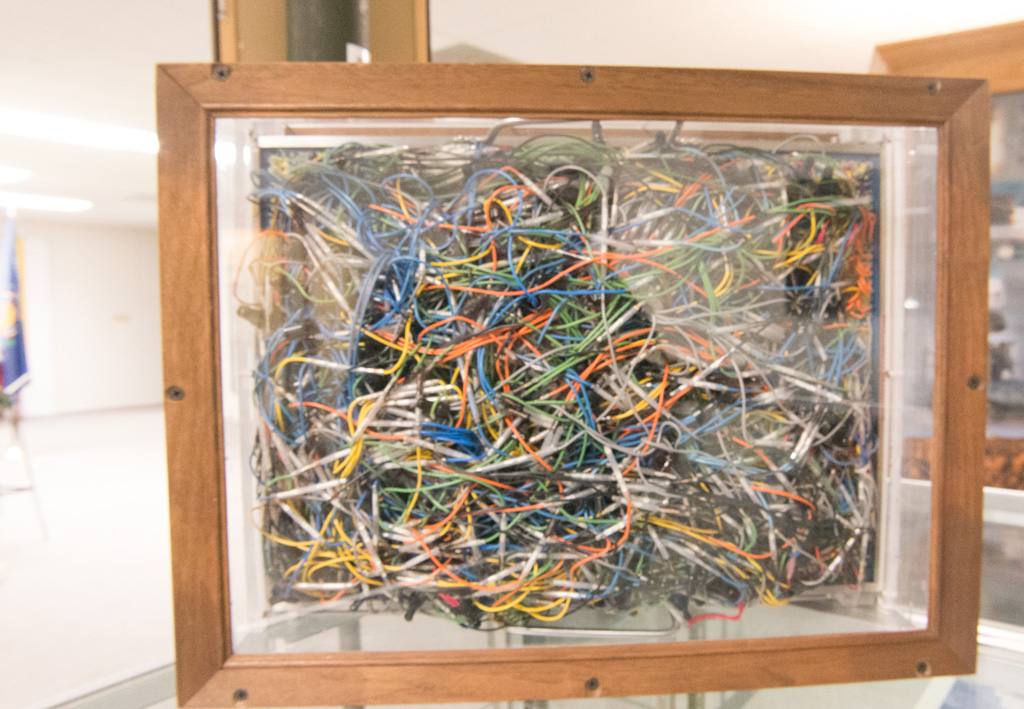

There was also a nice indoor portion of the museum. Part of it covered the computing resources used in the early days of the missile age. Here is a “patch panel” used to program a computer in the days before software. This is from a computer used into the ’70s!

One way of gathering data about test flights is to track the rockets visually, with “cinetheodolites.” Each of these required two operators, and many were used around the range.

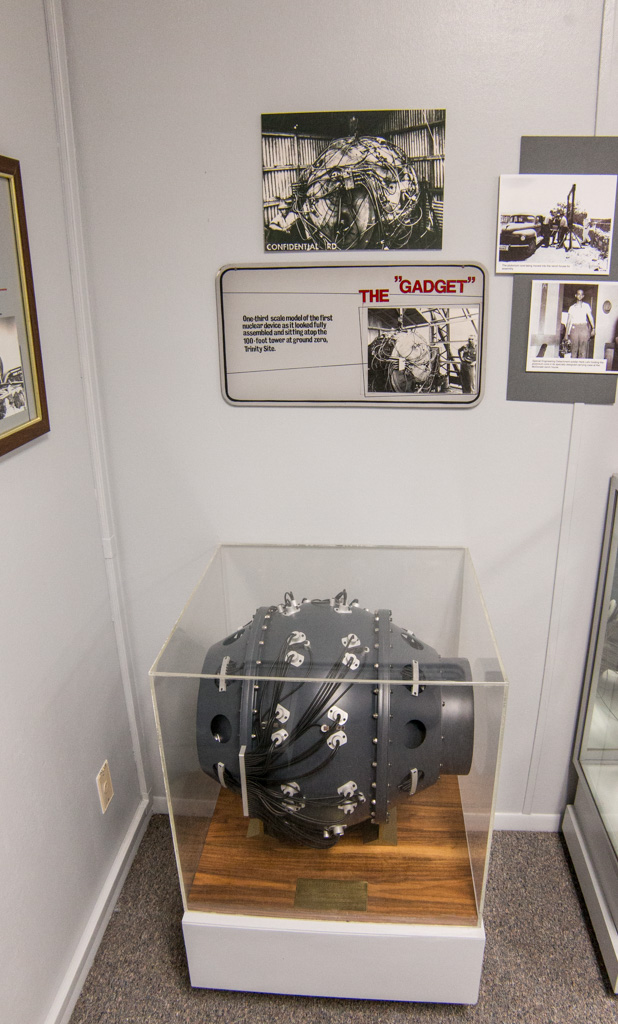

Trinity

There are moments that change the course of history forever; one happened here. On June 16, 1945, the world’s first atomic explosion happened on White Sands Missile Range, at the Trinity Site. The Trinity Site is only open to visitors twice a year so we weren’t able to see it first hand, but a good portion of the museum’s indoors display space is devoted to it.

The Trinity bomb was the same design as the second bomb, dropped on Nagasaki, Japan, to end World War II.

White Sands National Monument

On the second day, we went to the National Monument. Mile after mile of white “sand,” actually gypsum. After having seen the delicate gypsum florets in Mammoth Cave, it was amazing to see this much gypsum, literally piled up. Kathe thought it looked like we were on the moon!

It was interesting to walk on the dunes. I have lived near the water all my life except for our time in New Hampshire, and am used to walking on sand—including the sand dunes on North Carolina’s Outer Banks. The gypsum packs much more tightly than sand, and is very easy to walk on in comparison.

We went sledding down the dunes on a plastic saucer (like would be used on snow). Despite waxing the bottom of the saucer, other than the color of the dune’s surface, it wasn’t anything like sledding on snow! It was quite sticky, but once you got going, it was fun riding down the dune. Kathe got some good rides, but I fell out of the saucer each time! Unfortunately, I didn’t get any good video of me tumbling down the dune. (Sand-sky-sand-sky-sand-sky…)

The dunes are always moving, driven by the wind. Keeping the tourist area road open is a constant problem.

We had a really good day there, walking some trails and seeing the scenery. Al finished with a ranger-led walk just before sunset. The guide is an astronomer by training, working as a paleo-geologist. He described some of the research going on at the whole White Sands site, much of it outside the bounds of the Monument.

On the desert floor (where there isn’t currently a dune), the water table is only a foot or two below the surface. The geology of the area depends on this.

The yucca plant below may be 30 or more feet tall. It is rooted on the desert floor, and as a dune comes along it grows to keep its leaves and flowers above the level of the dune. Unfortunately, when the dune passes, the yucca can’t support its long stem. It collapses and dies.

You didn’t think I’d leave without a sunset shot, did you?

If you get a chance, do plan to go. White Sands National Monument is other-worldly. (Lunar?)